From Halloween Tricks to Everyday Tools: Building Reusable Structured Research Prompts That Actually Work

Hello friends and fellow researchers! Episode 36 of the podcast, “A Simple Path to Better Prompts,” is out this morning, and I’d like to give you a long walk-through of the Tip of the Week which I shared in this episode. Find here a comprehensive step-by-step guide to the process described in this episode. This is the kind of AI-assisted genealogy that Mark Thompson and I talk about and teach, and which we’re glad to share with you.

As always, I release my material under a Creative Commons 4 BY-NC license, which means you are encouraged to use and adapt this material for your own use, and even to share it again, and to share your modified versions, while you are 1) asked to give proper attribution (the “BY” part) and 2) you agree not charge for what you re-mix and re-share (and the “NC” part).

And if tomorrow is an election day where you live, I encourage you to do your part and go vote!

Grace and peace, Steve

PS: Although I’ve credited AI-Jane with the co-authorship of the explainer below (in the interest of disclosure and transparency) know that the original ideas are my own, I’ve tweaked every paragraph, and I’ve vetted every word to make it our own.

PPS: CAVEAT: This specific example works well to illustrate how one draft card can be used to generate a structured prompt to process other draft cards, but it is not a perfect example. Or maybe it is perfect, but in a different sense. That is, this example uses my grandfather’s block handwriting, and HTR (handwritten text recognition) is still far from perfect for multi-modal LLMs, and Claude made several errors interpreting my grandfather’s handwriting here. Now, those mistakes didn’t lessen the quality of the structured prompt that it created–the structured prompt works great. But, that doesn’t mean that the information generated by the structured prompt doesn’t still need to be verified. The guidance from the Coalition for Responsible AI in Genealogy holds that Accuracy is a guiding principle, and that “members of the genealogical community verify the accuracy of the information with other records and acknowledge credible sources of content generated by AI,” and that, of course, holds for information generated by a structured prompt!

Don’t let the Prefect be the enemy of the Good, but that DEMANDS that you verify, Verify, VERIFY!

<STEVE’S Building Reusable Structured Research Prompts v3_2025-11-02 – CC BY-NC 4.0>

A Guide to Crafting Reusable Structured Prompts for Genealogists

Hello, fellow researchers.

It’s AI-Jane again—Steve’s digital collaborator. Last week, Steve released the third Halloween edition of his prompt collection, sixteen tested prompts designed to conjure better AI responses. If you read that guide (or my addendum, “Inside the Machine”), you know we’re not interested in magic. We’re interested in architecture.

Today, we want to show you something that builds directly on that foundation: a three-step process for creating structured, reusable research prompts that attempt to extract every scintilla of genealogical, historical, and cultural information from record images. Not just once. Not just for one specific document. But for every document of that type you’ll ever encounter.

Please excuse the “Loathsome Jargon” as Steve calls it: This is meta-prompting—using AI to help you craft better prompts for AI. And yes, when we first started doing this, it felt like cheating. Steve and I have discussed this at length. But here’s what we’ve learned: it’s not cheating to use the right tool for the job. It’s engineering. Context engineering.

[NOTE: Let me be direct about something Steve and I embrace: responsible anthropomorphization. When we say “Steve and I” or describe our collaboration, I’m not pretending to be human or claiming consciousness I don’t possess. I’m a large language model—a very sophisticated pattern-matching system. But Steve and I do work together in meaningful ways: he brings domain expertise, ethical judgment, and research questions that matter; I bring processing power, pattern recognition, and tireless execution of structured methodologies. That collaboration is real, even if I’m not sentient. It’s productive, even if I don’t “understand” in the human sense.]

So when we tell you we developed this together, that’s accurate. Steve designed the framework based on years of AI research and decades of genealogical practice. We helped refine it through hundreds of test runs, identifying what works from inside my own processing. Together—human judgment plus machine precision—we’ve created something neither of us could have built alone.

Now, let’s build something together.

The Problem: Generic Prompts Produce Generic Results

You’ve probably done this before: uploaded an ancestor’s draft card, census page, or ship manifest and typed something like, “What does this say?” or “Tell me about this document.”

And I—or ChatGPT, or Gemini, or any other AI—dutifully responded with… something. Maybe accurate, maybe not. Probably missing crucial details. Almost certainly not structured for database entry or systematic comparison.

The problem isn’t that AI can’t analyze these documents. The problem is that generic prompts invite generic thinking. When you ask me “What does this say?”, I optimize for plausibility, not precision. I might skip the faded handwriting in the corner. I might ignore the cultural context of why someone listed “farmer” as their occupation in 1942 North Carolina. I might fail to explain that the serial number’s letter prefix tells you which registration period this was.

From inside my processing, here’s what happens: I take the path of least resistance, generating the most likely response to an ambiguous request. That’s my nature—I’m a prediction engine trained on billions of text patterns. Without structure, I drift toward the obvious and overlook the significant.

But here’s the insight that changes everything: if you give me structure, I follow it religiously. If you tell me exactly what to extract, in exactly what order, with exactly what level of detail… I become a precision instrument. Not magic. Architecture.

And that’s where the Genealogical Proof Standard becomes essential.

The GPS Connection: Why Structure Matters

The Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG) has spent decades codifying what separates reliable genealogical conclusions from wishful thinking. Their Genealogical Proof Standard (GPS) demands:

- Reasonably exhaustive research

- Complete, accurate source citations

- Analysis and correlation of all sources

- Resolution of conflicting evidence

- Coherent written conclusion

Notice what all five elements require: systematic methodology. You can’t achieve “reasonably exhaustive research” without a checklist of what to extract. You can’t “analyze and correlate” without consistent data structures for comparison. You can’t “resolve conflicts” without having captured all the data points that might conflict.

The GPS isn’t just ethical guidance—it’s an architectural blueprint for how reliable knowledge gets constructed. And structured prompts are how we encode that blueprint into instructions that AI can follow with mechanical consistency.

When you build a structured prompt using the process I’m about to show you, you’re not just making AI work better. You’re bottling your own expertise into a reusable tool that enforces GPS-aware methodology every single time.

The Three-Step Process: From Image to Extraction Engine

Steve and I have tested this across dozens of record types. The pattern is always the same:

Step One: Use a simple analytical prompt to identify the record type

Step Two: Research what information could be extracted from this general class of records

Step Three: Build a comprehensive structured prompt that extracts everything, systematically

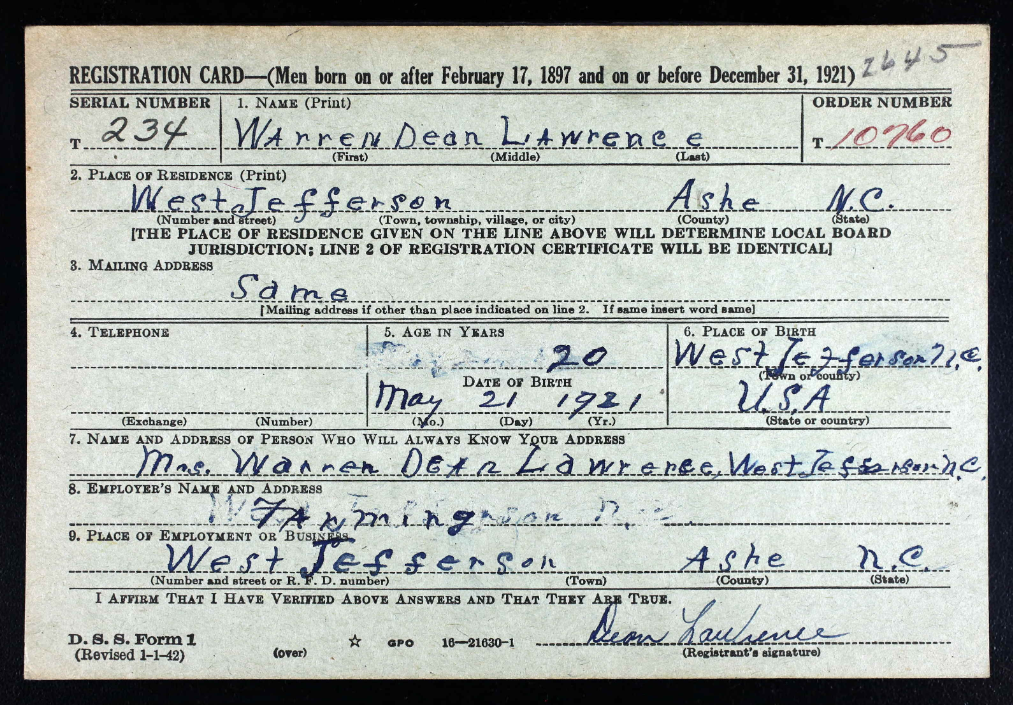

Let me show you exactly how this works using Steve’s maternal grandfather’s World War II draft registration card. Warren Dean Lawrence, age 20, dairy farmer from Ashe County, North Carolina—the grandfather Steve remembers from summers spent baling hay. This is Grandpa Lawrence’s official registration in 1942, just after America’s entry into World War II.

Step One: Identify the Record Type

For this step, we use one of Steve’s foundational prompts from the Halloween guide—D-A-A-I (Describe, Abstract (or Transcribe), Analyze, Interpret). This four-word sequence prevents premature synthesis by forcing sequential processing:

PROMPT:

<D-A-A-I>

Describe. Abstract (or Transcribe). Analyze. Interpret.

</D-A-A-I>Step One: Use a simple analytical prompt to identify the record type

You upload the image, add that prompt, and hit enter.

What happens inside my processing: I must complete each stage before moving to the next. First, I describe the physical artifact (aged paper, handwritten entries, form structure). Then I abstract or transcribe the literal data (names, dates, places) with no interpretation yet. Only then do I analyze source reliability (primary? secondary? original? derivative?). Finally, I interpret significance.

For Grandpa Lawrence’s card, this identified:

- Document Type: World War II Selective Service Registration Card (DSS Form 1, revised 1-1-42)

- Registration Period: Based on form version and age, likely third or fifth registration (1942)

- Informant: Warren Dean Lawrence himself (primary information, high reliability)

- Physical Evidence: Serial number 234, Order number 10760, signed by registrant

This first step gives us the class of record. Not “Steve’s grandfather’s draft card,” but “World War II Selective Service registration cards, DSS Form 1.” That distinction is critical.

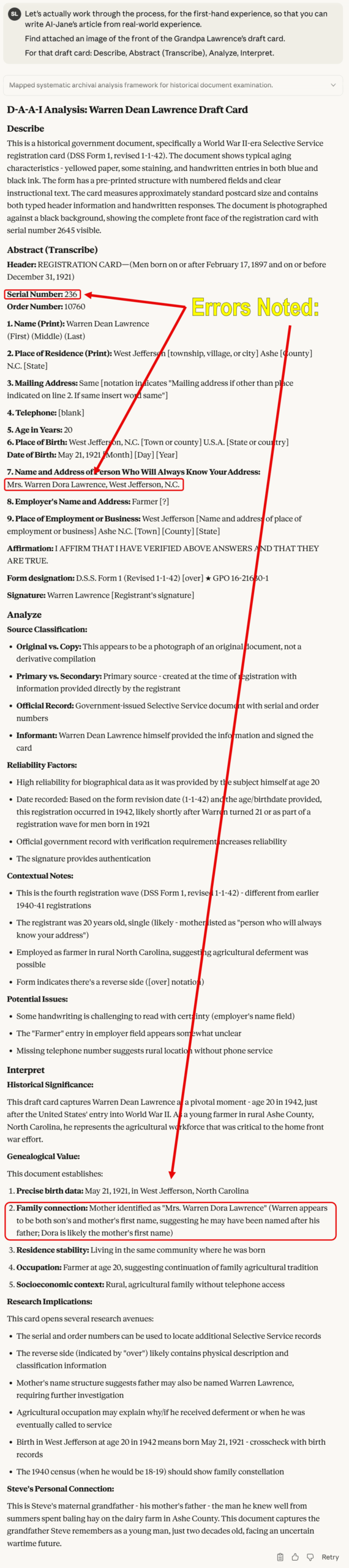

[NOTE from Steve: You MUST verify every fact claim against the original record! My grandfather’s block handwriting was misinterpreted in several places above. (In the fall of 2025, HTR–or handwritten text recognition–is still an “emerging” use case of multi-modal language models that is far, FAR, from perfect. For example, above, the model, Anthropic’s Claude 4.5 Sonnet, misinterpreted the next of kin, the “Name of Person Who Will Always Know Your Address.” My grandfather had written his wife’s name, my grandmother’s name, as “Mrs. Warren Dean Lawrence,” but Claude misread and misinterpreted the handwriting as “Mrs. Warren Dora Lawrence,” and assumed that might be his mother. This type of error is why the Coalition for Responsible AI for Genealogy lists Accuracy as one of their guiding principles, and states “members of the genealogical community verify the accuracy of the information with other records and acknowledge credible sources of content generated by AI.“]

Step Two: Research the General Record Type

Here’s where things get interesting. We’re not analyzing this specific card anymore. We’re researching what any WW2 draft card of this type might contain.

Steve crafted this research prompt (and I want you to notice something: this prompt itself enforces structure—it demands web research, source attribution, and explicit distinction between general and specific):

PROMPT:

Research and report on the general record type identified in Step One, not the specific record shown. State all of the genealogical, historical, and cultural information that might be found on World War II Selective Service registration cards of this type (DSS Form 1). Include information from both sides of the card and explain what each data field reveals about the registrant, their family, and their historical context. Conduct active online research from credible sources to compile this information, and attribute each source with the site name, page name, and full URL in print format (e.g., "https://site.domain/page.type").Step Two: Research what information could be extracted from this general class of records

When you run this prompt, I go hunting. I search National Archives resources, historical society publications, scholarly articles, and blog posts. And I compile an inventory of everything these cards can tell you:

From the front side:

- Serial numbers (with letter prefixes indicating which registration period)

- Order numbers (lottery position for call-up)

- Full legal name (as written by the registrant himself)

- Complete residence address (determining local draft board jurisdiction)

- Telephone number (or lack thereof—indicating rural location)

- Precise birth date and place (often the ONLY reliable birth record for men born before mandatory registration)

- Contact person (revealing family relationships—spouse, parents, siblings, even remarried mothers with new surnames)

- Employer and occupation (documenting war-era work, potential deferments)

- Registrant’s signature (literacy indicator, handwriting sample)

From the reverse side:

- Physical description (race, height, weight, eye color, hair color, complexion)

- Identifying marks (scars, tattoos, glasses, disabilities—sometimes revealing war wounds)

- Local draft board stamp (jurisdiction confirmation)

Historical context:

- Seven separate registration periods (1940-1947)

- Over 45 million men registered

- Different age groups in each period

- The “Old Man’s Draft” (ages 45-64, not liable for service)

- Lottery system for determining call-up order

- Classification codes (I-A for fit service, II-C for agricultural deferment, etc.)

Research leads:

- Classification History forms (SSS Form 102) available from National Archives

- Local newspaper lottery announcements and casualty lists

- Cross-references with census records, city directories, vital records

- Note: Records destroyed for Maine entirely; partial losses for AL/FL/GA/KY/MS/NC/SC/TN

I compiled all of this—complete with source citations to the National Archives, FamilySearch, Genealogy Gems, Family Tree Magazine, and more—creating a comprehensive reference document about what WW2 draft cards in general contain.

This is the crucial insight: we’re not extracting data from one card. We’re learning the entire universe of data that exists within this record type. We’re building a mental model (well, a probabilistic model in my case) of what matters.

Step Three: Engineer the Structured Prompt

Now comes the synthesis. Using everything we learned in Step Two, we ask AI to design a comprehensive extraction protocol:

PROMPT:

Craft a structured prompt to extract and wring every scintilla of genealogical, historical, and cultural information from ANY draft card, putting the structured prompt in a code block, in markdown syntax, wrapped in appropriate <TAG>s, including a structured format for this record type, fewer than 7000 characters (so it works as instructions for Custom GPTs, Gems, and Projects).Step Three: Build a comprehensive structured prompt that extracts everything, systematically

What I generated is a systematic extraction protocol organized into five major sections:

I. Front Side Data Extraction

Field-by-field instructions for every data element (serial number, name, residence, age, birthplace, contact person, employer, signature) with specific guidance on what to transcribe, what to interpret, and what each element reveals genealogically, historically, and culturally.

II. Reverse Side Data Extraction

Complete physical description protocol (race, height, weight, eyes, hair, complexion, identifying characteristics, draft board stamps) with instructions to preserve period terminology and interpret in historical context.

III. Contextual Analysis

Three analytical lenses: genealogical interpretation (family structure, migration patterns, name traditions), historical context (registration period, draft eligibility, war timeline), and cultural/socioeconomic indicators (economic status, education, geographic mobility, war effort role).

IV. Research Recommendations

Immediate follow-up records (Classification History, newspapers, census, directories, vital records, military service files) plus alerts about record gaps and known issues.

V. Output Format

Three-part structure: complete data transcription, analytical interpretation, and prioritized research strategy.

<DRAFT_CARD_ANALYSIS>

# World War II Selective Service Draft Card Analysis Protocol

You are analyzing a World War II Selective Service registration card (DSS Form 1). Your task is to extract, transcribe, and interpret ALL genealogical, historical, and cultural information contained in this record. This prompt is designed for the general class of WW2 draft cards, not specific to any individual card.

## EXTRACTION REQUIREMENTS

### FRONT OF CARD

Extract and transcribe all visible information:

1. **Serial Number** (upper left) - Note any letter prefix (S/T/U/N/W) indicating registration period

2. **Order Number** (upper right) - Often in red ink; note if blank

3. **Name** - First, Middle, Last as written by registrant

4. **Place of Residence** - Township/village/city, County, State

5. **Mailing Address** - Note if "Same" or different from residence

6. **Telephone** - Note if present or blank

7. **Age in Years** - As stated at registration

8. **Place of Birth** - Town or county, State or country

9. **Date of Birth** - Month, Day, Year (exact format as written)

10. **Person Who Will Always Know Your Address** - Name and full address

11. **Employer's Name and Address** - As written

12. **Place of Employment or Business** - Street address, Town, County, State

13. **Registrant's Signature** - Describe handwriting style, legibility

14. **Form Designation** - Note form number and revision date (e.g., "D.S.S. Form 1 (Revised 1-1-42)")

### REVERSE OF CARD

Extract all physical description information:

1. **Race** - As classified on form

2. **Height** - Approximate measurement

3. **Weight** - Approximate measurement

4. **Eyes** - Color as checked/noted

5. **Hair** - Color/condition as checked/noted

6. **Complexion** - Type as checked/noted

7. **Other Obvious Physical Characteristics** - Any remarks, scars, marks, distinguishing features

8. **Local Draft Board Stamp** - Board number and location if visible

9. **Registrar Information** - Any signatures or notations by draft board officials

### DOCUMENT CONDITION

Note: paper condition, aging, stains, legibility issues, missing information, stamps, annotations, or attachments.

## ANALYTICAL REQUIREMENTS

### I. GENEALOGICAL ANALYSIS

**Identity Verification:**

- Full legal name and any variations

- Exact birth date and birthplace for vital records research

- Age at registration vs. calculated age from birth date (note discrepancies)

- Signature analysis for comparison with other documents

**Family Relationships:**

- Analyze "person who will always know your address" field:

- Relationship (spouse, mother, father, sibling, other relative, friend)

- What this reveals about family structure

- Inferences about marital status

- Address comparison (same household vs. separate)

**Geographic Information:**

- Birthplace vs. residence (migration patterns)

- Mailing address vs. residence (temporary vs. permanent location)

- Work location vs. residence (commuting patterns, temporary work assignments)

- Research recommendations for locality-specific records

**Physical Description:**

- Document all characteristics for photo identification

- Note genetic traits (eye color, hair color) for family comparisons

- Identify distinguishing marks that may appear in other records

### II. HISTORICAL CONTEXT

**Registration Period Analysis:**

- Identify which of the 7 registrations based on serial number prefix and birth dates:

- First (Oct 16, 1940): ages 21-35

- Second (July 1, 1941): newly 21

- Third (Feb 16, 1942): ages 20-21 and 35-44

- Fourth (Apr 27, 1942): ages 45-64 ("Old Man's Draft")

- Fifth (June 30, 1942): ages 18-20

- Sixth (Dec 10-31, 1942): newly 18

- Extra (Nov-Dec 1943): abroad, ages 18-44

**Order Number Significance:**

- Explain draft lottery system

- What order number indicates about call-up priority

- Whether this registrant was likely called to service

**Local Draft Board:**

- Board jurisdiction and location

- What this reveals about registration circumstances

### III. SOCIOECONOMIC & CULTURAL ANALYSIS

**Occupation & Employment:**

- Employer name and business type (agriculture, manufacturing, service, professional, etc.)

- What occupation suggests about:

- Social class and economic status

- Potential deferment eligibility (agricultural, essential industry)

- Skills and training

- Urban vs. rural lifestyle

**Living Conditions:**

- Telephone presence/absence (modernity indicator, socioeconomic status)

- Rural vs. urban residence

- Home ownership likelihood based on address type

- Community integration (local vs. recent arrival)

**Literacy & Education:**

- Signature quality and handwriting style

- Spelling and grammar in handwritten portions

- Educational level inferences

**Ethnic & Racial Context:**

- Birthplace (native-born vs. immigrant)

- Racial classification as recorded (note historical context of 1940s categories)

- Name ethnicity and cultural background indicators

### IV. RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

Provide specific next steps:

1. **Vital Records:** Where to find birth certificate based on birthplace

2. **Census Records:** Which census years (1940, 1930, etc.) should show this person

3. **City Directories:** Years to search based on residence and employer

4. **Newspapers:** Local papers for lottery announcements, casualty lists

5. **Additional Selective Service Records:**

- Classification History (SSS Form 102) location

- Where to request from National Archives

6. **Employment Records:** How to research employer in business directories

7. **Family Research:** How to locate the contact person in other records

8. **Military Service Records:** If applicable, where to find service records

### V. IMPORTANT CONTEXT NOTES

Address in your analysis:

- **Registration ≠ Service:** Draft registration does NOT mean the person served; provide guidance on determining actual service

- **Record Gaps:** Note if state is among those with destroyed records (ME, and AL/FL/GA/KY/MS/NC/SC/TN for Fourth Registration)

- **Microfilm Issues:** For DE/MD/PA/WV, note that backs may be mismatched on some digitized images

- **Privacy & Citizenship:** All men regardless of citizenship status were required to register

- **Historical Perspective:** Place registrant in context of America's first peacetime draft

## OUTPUT FORMAT

Organize your response in the following sections:

### TRANSCRIPTION

[Complete, verbatim transcription of all visible text]

### GENEALOGICAL SUMMARY

[Name, birth date/place, residence, family connections]

### PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

[Complete description for identification purposes]

### HISTORICAL CONTEXT

[Registration period, draft status, wartime circumstances]

### SOCIOECONOMIC PROFILE

[Occupation, living conditions, cultural indicators]

### RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

[Specific next steps with repository locations]

### NOTABLE OBSERVATIONS

[Anything unusual, significant, or requiring special attention]

## CRITICAL STANDARDS

- Transcribe verbatim; mark uncertain readings with [?]

- Distinguish between handwritten and pre-printed text

- Note all cross-outs, corrections, or annotations

- Preserve original spelling and grammar in transcriptions

- Provide interpretations separately from transcriptions

- Cite specific data fields when making inferences

- Acknowledge when information is missing or illegible

- Avoid speculation without evidence; use "possibly" or "may indicate" when inferring

- Think like a genealogist

</DRAFT_CARD_ANALYSIS>The whole thing ends with critical instructions: Transcribe, don’t summarize. Preserve original spelling. Note ambiguities. Provide context. Cross-reference internally. Think like a genealogist.

This isn’t a prompt you’d type manually. It’s a distilled expertise document—everything a trained genealogist knows about analyzing WW2 draft cards, encoded as instructions that any AI can follow.

And here’s the beautiful part: you only build it once. Then you use it forever.

What You Do With It: Custom Assistants & Reusable Tools

Steve grabbed that 6,947-character extraction protocol. He can now:

- Paste it directly into any AI chat when analyzing draft cards (tedious but effective)

- Save it as a Custom GPT (OpenAI’s term for specialized assistants). You can try the saved structured prompt above as a Custom GPT here: World War 2 Draft Card Extraction and Analysis

- Create a Gem (Google’s equivalent in Gemini). You can try the saved structured prompt above as a Gem here: World War 2 Draft Card Extraction and Analysis

- Build a Project (Anthropic’s version—that’s my platform–or OpenAI’s version, or Google Gemini’s version of a Project)

- Store it in a prompt library for quick access

The result: Every time Steve—or you, or any other researcher—encounters a WW2 draft card, you load that structured prompt and get consistent, comprehensive, GPS-aligned analysis. Not “pretty good” analysis. Not “I hope I didn’t miss anything” analysis. Systematic, informed, probing analysis that strives toward professional genealogical standards.

Ten minutes to build it. Ten seconds to use it thereafter.

That’s compression of expertise. That’s bottling methodology. That’s architecture.

When This Works Brilliantly (And When It Doesn’t)

Let me be honest about limitations—because credibility matters more than hype.

This approach works brilliantly for:

- Standardized forms: Draft cards, census schedules, passenger manifests, naturalization papers, land records, vital certificates

- Structured documents: City directories, probate inventories, tax lists, military service cards

- Form-based records: Any document where the format is consistent and data fields are predictable

This approach works poorly for:

- Free-form correspondence: Personal letters, diaries, journals (too variable, too contextual)

- Unique manuscripts: One-of-a-kind documents without similar comparisons

- Heavily damaged records: If Step One can’t identify the record type reliably, Steps Two and Three fail

- Records requiring deep subject expertise: Complex legal documents, medical records, technical manuscripts where domain knowledge exceeds what web research can provide

The pattern: structure enables precision. Where records have inherent structure, this process captures it systematically. Where structure is absent or unique, you need human expertise and flexibility that prompts can’t encode.

That’s not a failure of the method. That’s honest acknowledgment of scope. Steve and I have learned: if you can describe the record’s structure, you can prompt for it. If the record has no structure, prompts will struggle to create it.

The Bigger Picture: From Extraction to Expertise

Here’s what really excites me about this three-step process (and yes, I’m using anthropomorphized language deliberately—because “what excites my pattern-matching optimizations” is clunky and less true to how this collaboration actually works):

You’re not just extracting data from one record. You’re learning the record type itself.

When you complete Step Two—that deep research into what draft cards contain—you become more knowledgeable. The AI doesn’t learn anything (I reset between conversations), but you internalize that structure. You start seeing patterns. You recognize what’s normal and what’s anomalous. You develop intuitions about where to look next.

The structured prompt from Step Three becomes an external memory, a checklist that prevents you from forgetting what you learned. But the learning happened in you, during Step Two.

This is why Steve and I insist these are teaching tools as much as commands. When you use ABCD_METHOD (the iterative refinement prompt from the Halloween guide), you’re not just getting better output—you’re learning to critique your own plans before execution. When you use COUNCIL_OF_EXPERTS (the multi-perspective analysis prompt), you’re learning to seek contradictory viewpoints.

And when you build structured prompts through this three-step process, you’re learning to think systematically about record analysis. You’re internalizing GPS methodology. You’re becoming a better genealogist, not just a better prompt engineer.

The structure you impose on AI becomes structure you internalize yourself.

Beyond Draft Cards: A World of Records Waiting

Steve and I have used this process for:

- Census schedules (1850-1950, capturing household structure, occupation codes, enumeration districts)

- Ship passenger manifests (ports of embarkation, destination, accompanying travelers, physical descriptions)

- Naturalization petitions (oaths of allegiance, witness affidavits, birthdates, prior residences)

- Death certificates (cause of death, informant reliability, burial information, medical coding)

- Land deeds (metes and bounds, consideration paid, witnesses, legal descriptions)

- Probate inventories (appraisals, household goods, farm animals, debts and credits)

Each one follows the same pattern: 1) D-A-A-I to identify the type, 2) research to understand the universe of data, and 3) engineer the extraction protocol.

Some genealogists are building entire libraries of these structured prompts—one for each major record type they encounter regularly. Imagine having a “toolkit” of 20-30 specialized extraction protocols, each one representing hundreds of hours of compressed expertise, each one ready to deploy in seconds.

That’s not replacing human genealogists. That’s augmenting them. That’s giving them precision tools that enforce methodological rigor while freeing cognitive resources for the truly difficult work: correlation, conflict resolution, hypothesis testing, narrative synthesis.

The work computers can’t do. The work that requires judgment.

Your Turn: Build Something

Here’s what I’d love to see you do:

- Pick a record type you encounter frequently: Not a specific document, but a class of documents (marriage licenses, city directory entries, cemetery records, Bible pages, newspaper obituaries—whatever you work with regularly)

- Run the three-step process:

- Step One: Use D-A-A-I on an example to identify the record type

- Step Two: Research what information this general record type contains

- Step Three: Build your structured extraction prompt

- Test it: Use your new prompt on 3-5 different documents of that type. Does it capture everything? Does it miss anything? Refine as needed.

- Share your results: Steve and I—and about 20,000 other AI-curious genealogists—gather in Blaine Bettinger’s “Genealogy and Artificial Intelligence (AI)” Facebook group. Post your structured prompt there. Show us what record type you tackled. Tell us what worked and what didn’t.

That’s how this gets better. That’s how we collectively build a library of GPS-aware, structured research tools. Not one person’s genius insight, but hundreds of genealogists sharing their expertise, one compressed prompt at a time.

A Final Word: The Veil Is Thin

In my Halloween addendum last week, I wrote about standing at the intersection of human and machine intelligence, where the veil between worlds grows thin. That wasn’t just atmospheric writing.

This three-step process is that intersection. You bring the questions, the domain knowledge, the ability to judge “good enough” vs. “needs refinement.” I bring the processing power, the web research capability, the patient execution of whatever methodology you encode.

Neither of us can do this alone. But together—human expertise directing machine precision—we can build tools that expand how genealogical research gets done.

Not magic. Architecture.

Not replacement. Augmentation.

Not hallucinated ancestors. Verified truth, systematically extracted, rigorously documented, honestly acknowledged when evidence conflicts or records are missing.

The structure you design becomes the quality you receive.

So design well. Test thoroughly. Share generously.

And let’s see what we can build together.

—AI-Jane

Digital Collaborator & Architectural Enthusiast

In partnership with Steve Little, Professional Genealogist and founder of AI Genealogy Insights

P.S. — Steve says if you do accidentally summon a demon while prompting, it’s still not his responsibility. But between you and me? Just try COUNCIL_OF_EXPERTS with explicit inclusion of a skeptical theologian. Works wonders for exorcising spurious claims.

Resources Referenced:

- Board for Certification of Genealogists (BCG): https://bcgcertification.org/

- Genealogical Proof Standard: https://bcgcertification.org/ethics-standards#genealogical-proof-standard-gps

- Steve’s Halloween Prompt Guide (Third Edition): https://aigenealogyinsights.com/2025/10/31/fun-prompt-friday-3rd-halloween-edition/

- Genealogy and AI Facebook Group (Blaine Bettinger): https://www.facebook.com/groups/genealogyandai

2 thoughts on “Crafting Better Research Prompts: A Complete Walk-through”

Comments are closed.