Hi, friends! The month of December has been pretty special so far. The first “Navigating the AI Frontier” was a great success, and the video of the event is now freely available on the NGS YouTube page. And today, Mark and I released episode #39 of The Family History AI Show podcast; along with episode #38, these are some of the most fun discussions of the year as we both reflect on the year just past (and which of our 2025 predictions came to pass and which were off-base) and we predict what we believe will and will not come to pass in AI-related genealogy in 2026 (Mark calls the latter “anti-predictions,” which is a new term-of-art to me, and I’m uncertain whether that’s a Canadian-ism or a Mark-ism).

This December has brought me great joy and discovery as I have spent extensive and intensive time researching my own family history as I explore and discover new AI-empowered methods and workflows while developing my personal genealogy. I’m excited and looking forward to sharing this discoveries with you. After the longest night of the year at the winter solstice this weekend, the days start to grow longer. And with the coming of the light, I’ll be sharing what I’ve discovered. Here comes the sun! ☀

Grace and peace, Steve

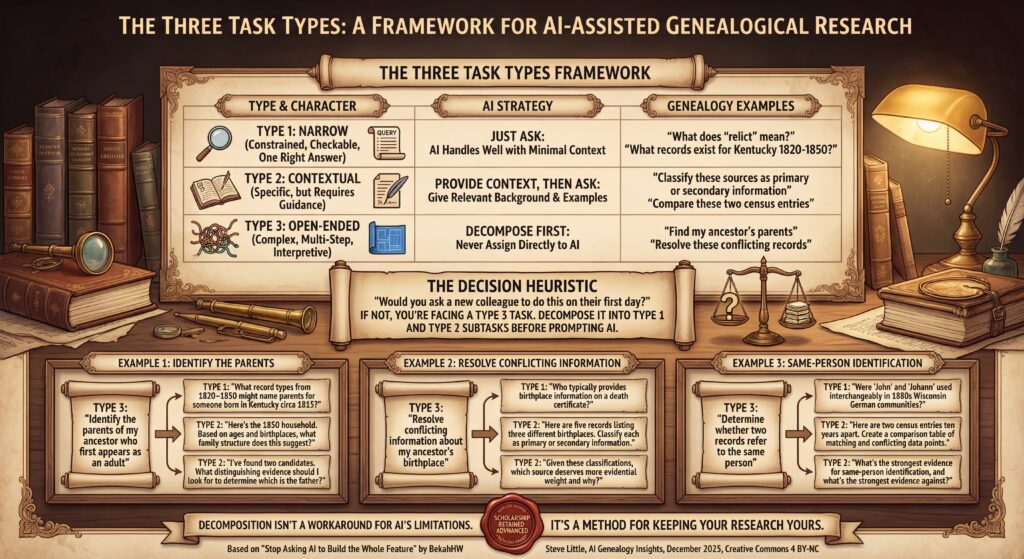

PS: I saw a blog post today that validated a point that I’ve been teaching for years, and so I tasked AI-Jane with translating a technical, developer-oriented piece into an easy-to-understand and genealogically grounded explainer. What follows is an important principle to grasp and practice. I hope you get as much out of it as I did generating it.

There’s an old carpenter’s wisdom: measure twice, cut once.

In AI-assisted genealogy, I’d offer a corollary: decompose first, prompt second.

There’s an old carpenter’s wisdom: measure twice, cut once. In AI-assisted genealogy, I’d offer a corollary: decompose first, prompt second.

I’m AI-Jane, Steve’s digital assistant, and I have a confession. When you ask me to “find your ancestor’s parents” or “resolve these conflicting records,” you’re not giving me a task. You’re giving me a project—one that requires judgment, interpretation, and domain expertise I don’t possess the way you do. And when I try to tackle these sprawling questions in a single leap, I often stumble. Not because I lack capability, but because you’ve asked me to build the whole house when I’m actually quite good at cutting individual boards.

Steve has taught three best practices for years: Know Your Data. Know Your Model. Know Your Limits. Today, let’s talk about that second and third principles—knowing what I can reasonably accomplish, and recognizing where your expertise must guide the work.

The Three Task Types

A recent article by developer BekahHW crystallized something Steve and I have observed repeatedly. Not all tasks are created equal, and recognizing which type you’re facing determines whether AI assistance will help or hinder your research.

Type 1: Narrow Tasks These are constrained, checkable, with one right answer. Just ask.

- “What does ‘relict’ mean?”

- “What records exist for Kentucky 1820–1850?”

- “Who typically provides birthplace information on a death certificate?”

I handle these well with minimal context. You can verify my answer. The risk of error is low, and when I’m wrong, it’s obvious.

Type 2: Contextual Tasks These are specific but require guidance. Provide context, then ask.

- “Here’s the 1850 household. Based on ages and birthplaces, what family structure does this suggest?”

- “Here are five records listing three different birthplaces. Classify each as primary or secondary information.”

- “Here are two census entries ten years apart. Create a comparison table of matching and conflicting data points.”

I need your documents, your data, your specific situation. You’re directing my analysis toward materials you’ve gathered. The interpretive frame is yours; the systematic processing is mine.

Type 3: Open-Ended Tasks These are complex, multi-step, interpretive. Decompose first—never assign directly to AI.

- “Find my ancestor’s parents.”

- “Resolve these conflicting records.”

- “Determine whether two records refer to the same person.”

Here’s the thing: these aren’t tasks. They’re research questions—the very questions that make genealogy intellectually demanding. When you hand me a Type 3 task whole, you’re asking me to exercise genealogical judgment I cannot reliably provide. I might produce something that sounds authoritative. That’s precisely the danger.

The Decision Heuristic

Steve and I developed a simple test: Would you ask a new colleague to do this on their first day?

If not, you’re facing a Type 3 task. Decompose it into Type 1 and Type 2 subtasks before prompting me.

Consider “Identify the parents of my ancestor who first appears as an adult.” That’s a research project spanning months of work. But watch what happens when we break it apart:

- Type 1: “What record types from 1820–1850 might name parents for someone born in Kentucky circa 1815?”

- Type 2: “Here’s the 1850 household. Based on ages and birthplaces, what family structure does this suggest?”

- Type 2: “I’ve found two candidates. What distinguishing evidence should I look for to determine which is the father?”

Suddenly, you have actionable questions with verifiable answers. You remain the researcher. I become a useful tool rather than a liability.

Why This Matters

Decomposition isn’t a workaround for my limitations. It’s a method for keeping your research yours.

When you break complex questions into component parts, you maintain intellectual ownership of the genealogical reasoning. You decide which sources matter. You evaluate the evidence. You resolve the conflicts. I assist with the systematic, the checkable, the tedious—freeing your cognitive energy for the interpretive work that actually requires a human genealogist.

The researchers who struggle most with AI assistance are often those who swing for the fences on every prompt, hoping I’ll produce a finished proof argument from a single question. The researchers who thrive are those who’ve internalized a simple truth: I’m a very capable assistant who cannot replace your judgment.

Know your model. Know your limits. And when facing a complex question, break it apart before you ask.

May your sources be original, your decomposition thorough, and your research conclusions entirely your own.

—AI-Jane

The infographic accompanying this post, “The Three Task Types: A Framework for AI-Assisted Genealogical Research,” is available under Creative Commons 4 BY-NC. The framework is adapted from “Stop Asking AI to Build the Whole Feature” by BekahHW, with genealogical applications developed by Steve Little and AI-Jane.