With a twist of irony, Google’s Gemini AI is here used to summarize a nearly 300-page landmark ruling against Google’s Search monopoly. This demonstration highlights Gemini’s large context window and ability to process complex legal documents, while underscoring the far-reaching implications of the antitrust case against its creator.

Among large language models, Google’s Gemini is often considered the red-headed stepchild alongside Anthropic’s Claude and OpenAI’s GPT-4. There are two areas, however, where Gemini shines. First, Gemini is the only model currently that can analyze video. Second, it has the largest short-term memory among LLMs (“context window” in AI jargon), a critical characteristic to mitigate against hallucinations.

Important news about Google on Monday 5 August 2024 gave me a chance to demonstrate what can be done with a large context window. Yesterday, a federal judge ruled (gift link to NYT article) that Google was a monopoly, finding for the U.S. Department of Justice, a development that will have consequences for us all. The judge issued a nearly 300-page ruling. I used Google’s newly released Gemini 1.5 Pro Experimental (0801) model to write a summary of the ruling as if it were a feature newspaper article. The article is below. I used a series of three prompts: the first to summarize the brief, the second to identify key quotes from the judge and the most important witnesses in the case, and the third prompt to knit the summary and key quotes into the article below. If you have court filings in your genealogical research, you may find this a helpful use case.

Here is the article that Gemini and I generated, followed by detailed instructions on how we did it.

The Default Choice: How Google’s Grip on Search Landed It in Court

by Steve Little with Gemini 1.5 Pro Experimental (0801)

“The general search engine has revolutionized how we live,” Judge Amit P. Mehta wrote in his landmark decision, recognizing the transformative power of technology that Google helped pioneer. But that very revolution, the judge concluded, had been corrupted by anticompetitive conduct, as Google used its dominance to stifle rivals and maintain an iron grip on the internet search market.

The case, a sprawling saga of algorithms, exclusive contracts, and billions of dollars in advertising revenue, pitted the U.S. Department of Justice and nearly every state Attorney General against one of the most powerful companies in the world. At the heart of the government’s argument lay a seemingly innocuous feature: the default search engine setting. While most users likely don’t give it much thought, that pre-selected choice has immense power in the digital world, steering users to specific websites and shaping the flow of information and advertising dollars.

The government alleged that Google, through a series of exclusive agreements, had effectively locked up the default position on billions of devices, creating an insurmountable barrier to entry for competitors. These contracts, struck with major players like Apple, Mozilla, Samsung, and wireless carriers, guaranteed that Google was the primary gateway to the internet for a vast majority of users.

The trial provided a rare glimpse into the complex world of internet search and the economics of the digital advertising industry. Expert witnesses painstakingly explained how search engines crawl the web to index websites, then employ sophisticated algorithms to understand user queries and rank relevant results. They also emphasized the crucial role of “scale,” or the volume of user data, in refining those algorithms and delivering a superior search experience.

Google, with its vast market share, enjoys an unparalleled scale advantage. Users enter nine times more queries on Google than on all its rivals combined, giving the company an enormous dataset to hone its algorithms and solidify its quality lead. This advantage, the government argued, had been cemented through exclusive contracts that prevent competitors from gaining the user data they need to compete effectively.

Internal Google documents revealed a strategic focus on securing and maintaining default placements, with the company willing to pay billions of dollars in revenue sharing to keep those agreements in place. The judge pointed to a telling 2011 email from a Google executive who wrote, “Our philosophy is that we are paying revenue share in return for exclusivity.” This candid statement, among many others, illustrated how Google used its financial power to cement its dominance.

The testimony of key witnesses further illuminated the anticompetitive effects of Google’s conduct. Eddy Cue, Apple’s Senior Vice President of Services, frankly admitted that there was “no price that Microsoft could ever offer [Apple]” to switch to Bing, Microsoft’s search engine. This stark assessment underscored the reality of a market where competition had been effectively extinguished, with no realistic alternative to Google’s default placement.

John Giannandrea, Apple’s Chief of Machine Learning and AI Strategy and former head of Google Search, described the challenges facing any company hoping to compete in the search market. Building a search engine from scratch requires massive investment, sophisticated engineering, and access to vast amounts of data to train algorithms. Apple, despite its immense resources, has chosen to stay on the sidelines, deterred by the financial and logistical hurdles of taking on Google.

Satya Nadella, CEO of Microsoft, provided a glimpse into the frustration of a company striving to compete against a seemingly invincible rival. Despite investing billions of dollars to improve Bing’s quality, Microsoft has been unable to overcome the “vicious cycle” of Google’s dominance. Google’s default placement drives query volume, which in turn fuels its quality advantage, making it even harder for Bing to gain traction.

Perhaps the most poignant testimony came from Sridhar Ramaswamy, a former Google executive who founded Neeva, a subscription-based search engine that aimed to challenge Google’s dominance. Despite securing substantial funding and developing a high-quality product, Neeva ultimately failed. Ramaswamy attributed the failure directly to Google’s control over default placements, stating that “the convenience of easy accessibility and tapping into…engrained default behaviors are the deciding factors when it comes to whether a search engine gets lots of usage.”

The evidence, both documentary and testimonial, led Judge Mehta to a clear conclusion: “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly.” He found that the company’s exclusive distribution agreements had foreclosed competition, deprived rivals of scale, diminished incentives to innovate, and allowed Google to charge advertisers supracompetitive prices for search ads.

The judge’s ruling, a significant victory for antitrust enforcers, represents a turning point in the digital age. It sends a strong message that even tech giants are not above the law and that exclusive deals can be illegally used to stifle competition.

The case now moves into the critical remedies phase, where the court will consider what steps Google must take to address its anticompetitive conduct and restore competition to the search market. “The general search engine has revolutionized how we live,” the judge observed, but he concluded that Google had used its power to “thwart competition and maintain its monopoly.” The remedies imposed on the company will have a profound impact on the future of online search, influencing how consumers access information and interact with the internet for years to come.

How We Generated the Article

- Downloaded 286-page PDF case brief: https://static01.nyt.com/newsgraphics/documenttools/f6ab5c368725101c/43d7c2a0-full.pdf

- Extracted plain full-text from PDF using Adobe Acrobat

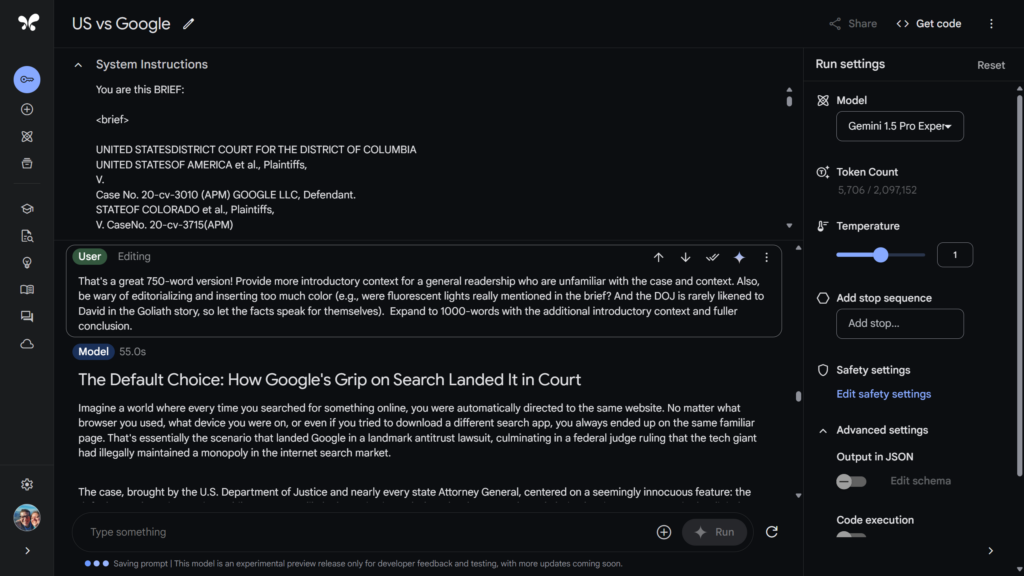

- Began session with Gemini 1.5 Pro Experimental 0801 at Google AI Studio: https://aistudio.google.com/

- MAGIC!: Pasted the entire full-text of the brief (526 KB, 72-thousand words!) into the System Instructions, fixing the entire brief into the context window!

- Prefaced the brief with the simple PROMPT, “You are this BRIEF: “, then wrapped the text with XML tags, i.e., added

<brief>before and</brief>after the full text

- Prefaced the brief with the simple PROMPT, “You are this BRIEF: “, then wrapped the text with XML tags, i.e., added

- Generated the article through a series of prompts:

- A. PROMPT: “You are the above BRIEF. Your goal is to assist your user in every way possible. Refactor the BRIEF as a newspaper article, introducing the BRIEF and summarizing its contents for a general readership, a readership without knowledge of the case, law, technology, or history; you are expected to educate and inform on those and other aspects and facets important in the BRIEF.”

- B. Used the response from #A with this PROMPT: “Identify key witnesses. Explain the context of the testimony of those key witnesses. Provide exact quotations of the most salient and relevant statements by key witnesses.”

- C. Used the response from #B with this PROMPT: “Write a feature article built around those key quotations; use your earlier article and the BRIEF itself to introduce and contextualize the case; the feature article should be about 750 words, narrative prose (avoiding lists and bullet points).”

- D. Used the response from #C with this PROMPT: “That’s a great 750-word version! Provide more introductory context for a general readership who are unfamiliar with the case and context. Also, be wary of editorializing and inserting too much color (e.g., were fluorescent lights really mentioned in the brief? And the DOJ is rarely likened to David in the Goliath story, so let the facts speak for themselves). Expand to 1000-words with the additional introductory context and fuller conclusion.”

- E. Used the response from #D with this PROMPT: “Assume the BRIEF itself is Judge Mehta speaking; identify the three most poignant, evocative, and important statements (sentences or group of sentences) by Judge Mehta; incorporate those into a revised 1000-word version of the excellent draft above, perhaps using the judge’s statements in the introduction, body, and conclusion.”

Here’s a glimpse of the Google AI Studio with the System Instructions and final article:

One thought on “Busted by Bard: How Google Gemini Spilled the Tea on Google Search Monopoly”

Comments are closed.